When there’s chaos in ML, Ivy steps up as the chosen one?

The world of machine learning has become quite turbulent in recent years. With the rise of frameworks such as Google’s TensorFlow and JAX, Meta’s PyTorch, Numpy, MXNet, and other machine learning frameworks such as Scikit-Learn, a new era of ML has emerged, heavily dominated by specific company’s programming philosophy. TensorFlow was the most popular framework used in the research, but has fallen out of favour in recent years in favour of PyTorch. Where TensorFlow falls short in being less pythonic or difficult to debug, PyTorch excels in its pythonic approach and ability to debug the code more effectively. It is also rumoured that Google has been using JAX in favour of TensorFlow for it’s own internal research work. Whatever the current state of these companies are, their ML frameworks will either become popular or fade into obscurity. Ivy is a project that aims to address the industry’s current state of chaos.

What Ivy is attempting to accomplish is:

-

Not an easy task, and

-

A much-needed attempt to fix this problem. In layman’s terms, Ivy is a framework-agnostic approach to building ML programs that run on top of popular ML frameworks we talked about earlier. Personally, I too have experienced this problem of conflicting frameworks in my own research endeveours and would have highly appreciated working with something like Ivy.

How does Ivy work?

Currently in their development phase, Ivy’s aim is to become a one stop shop for all of your ML code worries. To achieve this, they are first standardising the way we write ML code. Every industry at some point needs some form of standardisation, which the ML frameworks usually lack as evidenced by the above examples. For this, Ivy is adopting the Consortium of Python Data API Standards which itself is backed by industry leaders like Google, Meta, Microsoft, and many more.

Ivy is positioning itself as both an independent framework and a transpilation layer between two completely different ML frameworks. The first, it achieves by building on top of existing frameworks as a new abstraction layer, fixing the syntactic differences and making sure that regardless of the framework of choice using ivy.set_backend('<framework>'), the result is consistent. The second option is more naunced and complicated to achieve, which employs the use of graph compilers. In a nutshell, a graph compiler takes a deep neural network, compresses it, streamlines its operation so that it can run faster and consumes less memory.

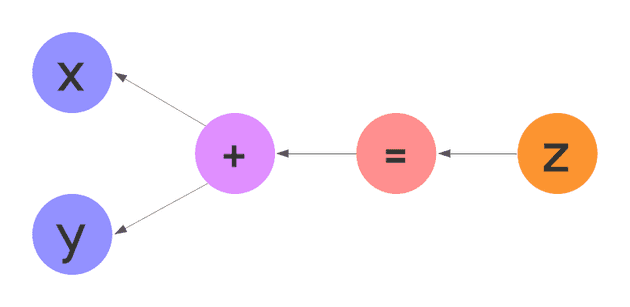

For example, x + y = z can be represented by the graph compiler as shown in this figure. However, please note this is a very simplified representation and in practise, it is much more complicated!

This type of graph representation can be extracted from any of the backends that Ivy currently supports using ivy.compile_graph and converted to any other framework using ivy.to_backend('<framework>').

Conclusion and final thoughts.

As I was hopefully able to show, Ivy seems to be very promising. It’s strategic position as both a framework and a transpilation layer is quite smart which might be the reason for it’s eventual wide market adoption. I believe academia will definitely benefit a lot from Ivy as a ton of time can now be used to do actual research vs. rewriting hundreds of lines of code and I can genuinely see wide adoption in these circles in the next few years. As for industry adoption, Ivy isn’t marketing itself as a replacement for TF, Torch, or JAX, just as a functionality built on top of these things, which is a good start. How would researchers in these companies react to Ivy will solely depend on the quality of transpilation, which will lead to a reduction in R&D overhead. Only time can tell how this will pan out!